|

In my latest YouTube video I show you a multi muscular movement workout which is easy to do. It incorporates eccentric, concentric and isometric exercises. These develop greater power and also resilience - so they are great at combatting injury.

You’ll see box to box jumps, drop and block jumps with added weight, and isometric squats and hamstring bridges, for example. We will often do this workout in season as it does not have a too draining effect on muscles or mind. It’ll often be a part of our Saturday workout when there are no comps. In terms of reps and sets we’re looking at 3-4 x 6 reps of the jump exercises and 3-4 sets of the eccentric ones with some variation (where relevant) with the angles or limbs positions held. Holds are around 10sec. If you’ve any specific questions then let me know. Jargon buster: Eccentric - muscular lengthening Concentric - muscular shortening Isometric - no muscular action

0 Comments

DO YOU REALLY NEED TO DO SQUATS? If I were to say to coaches of athletes in a range of sports from football to sprinting to rugby to martial arts to marathon running, that their athletes shouldn’t squat, I’d probably be run out of town (as fast as my non-significantly squat trained legs would allow!). I can hear the cry already, ‘Squats are a must-do; they’re a fundamental part of sports conditioning’.

However, it’s possible to argue that squats are perhaps over-rated and their value to actually enhancing sprint speed, particularly in the training mature athlete (i.e. when an athlete has developed considerable ability to bend and extend their knees against resistance) questionable. In the beginning God created the Squat The movement of bending and straightening our legs (using the ankle, knee and hip joints) known as flexion and extension respectively is a fundamental human movement. Hundreds of everyday actions require a squat, the most obvious being sitting and getting up out of a chair. The resisted squat as used in sports conditioning, i.e. with added weight (for example, with barbells, barbell and chains, dumbbells and powerbags for example), can be found in the majority of athletes’ training routines. These exercises are normally performed with a concentric muscular action emphasis. This means that the muscles of the ankle, knee and hip joints shorten under load to move the weight. Squat jumps can also be included in this category where the athlete lowers, perhaps holding dumbbells at arms’ length or a barbell across their shoulders and then rapidly extend their thighs to leap into the air. This is a dynamic exercise I really like. There are numerous other squat variations, such as single leg squats, Bulgarian split squats and single leg squats, however, the focus of this post is largely placed on the double leg back squat. Coaches from virtually all sports prescribe the squat in the conditioning routines of their athlete and for valid reasons. The action of extension and flexion is fundamental to running and jumping. On foot-strike during the gait cycle a runner’s knee’s will be flexed ready to absorb and transfer ground forces to propel the athlete forwards by means of rapid extension of the ankle, knee and hip. So we can see how easily the squat can be viewed, for example, as a sprint mirroring exercise. Over-cooking squats Many sprint coaches and athletes will be familiar with developing significant squat strength as manifested in 1 rep max ability, but conversely fail to see direct improvement in what really matters sprint speed. Now there are a number of potential reasons for this: 1. The Closeness of the Squatting Action to What’s Actually Required when Sprinting Sprinting is a unilateral activity, the normal squat bilateral. A sprinter’s foot will only be in contact with the ground for 0.089 of a second or so when they are flat out and traveling at 11-12m/s for elite men - and in that blink of an eye they have to impart and overcome force equal to two-three times their body weight. And they will need to transfer the vertical absorption of force into a horizontal push through optimum sprinting biomechanics to get to the line as fast as possible. Can you think of a time when you or an athlete you have coached has achieved those parameters when squatting? An athlete weighing 80kg would have to shift potentially 240kgs in that nanosecond! So, it’s very unlikely. Now, equally crucially in terms of what I am going to argue later on, how are the dominant muscles in the squat (the quads), relating to the other key muscles involved in sprinting, notably the hamstrings and hip-flexors. The actual contribution of these latter muscles to the squat, although used in the exercise’s action are much reduced in comparison to what's required when sprinting – again of which more later. Relevance of Muscular Actions Unless there is an attempt on the part of the athlete to lower and drive up out of the squat movement as fast as possible, the stretch-shortening cycle will not really be tested in the way that they are during sprinting (and even if this is done the match will be minor rather than major). Considering the hamstrings – a similar stretch, followed by a rapid contraction is fundamental to the late swing phase in the running cycle, when the lower leg is pulled back toward the track ready for foot-strike. Additionally the degree to which the hamstring is lengthened with significant force being generated at both its poles is very different. These actions/requirements are not a part of the squat, although the hamstrings are engaged during the eccentric phase. A very similar argument can be forwarded for the hip flexors – of which more later. Sprinting is a plyometric activity. The 100m distance is normally completed for elite men using 41-45 steps. On each and every one of these the muscles (and other soft tissue) will be required to catapult the sprinter forwards. On foot-strike the musculotendon structures of the ankles, knees and hips will be put on stretch and then they will contract virtually instantaneously and in doing so will generate great power (also known as the stretch-shortening-cycle). As noted the squat is a primarily concentric movement. Now, it is true that greater concentric power will boost sprint speed (particularly in new to sprinting athletes and in terms of enhanced acceleration, of which more later), however, once a basic level of extensor-derived quad strength is developed the role of the squat becomes significantly reduced as a sprint speed enhancer. As touched upon much research also suggests that heavy load squats have more of a relevance to conditioning acceleration rather than flat out speed. RESEARCH American researchers looked at the relationship between body weight, 1RM squat and 5,10 and 40 yard times (1). Seventeen male US Football players participated in the survey and they were divided into groups in relation to their 1RM squat and their body mass. Squats were tested to a degree of flexion of 70-degrees and power-to-weight ratio calculated. Sprint times were assessed by way of timing gates. Perhaps not surprisingly it was found that the athletes with the superior power-to-weight ratios had faster times at 10 and 40 yards. It’s important to consider power-to-weight ratio in the light of ultimate sprint performance ability and squat training protocols. If an athlete regularly trains using a 4-6 set x 8-10 rep protocol, using weights in the 70-85% 1RM ranges then the workout will elicit a significant androgen response. This will likely result in weight gain through muscle hypertrophy, due to the copious amounts of the stimulatory hormones being produced - testosterone and growth hormone. Thus coach and athlete must be mindful of the squat protocols they employ (and for other similar exercises and always be aware of body weight increases and its affects on power to weight ratio). Hip-flexor Importance Research backs up the notion of the importance of the hip flexors when it comes to sprinting. A Japanese team specifically looked at the contribution of the psoas major and thigh muscularity on the 100m times of junior sprinters (4). The research comprised of 44 sprinters (22 male and 22 female) aged 14-17. The cross sectional area of the quadriceps femoris, hamstrings and psoas major were analysed using magnetic resonance imaging. The average of left and right sides was calculated and this was related to 100m performance from official races. It was discovered in both genders that the faster sprinters had a greater development of the psoas major in comparison to the quadriceps femorsis muscles. Absolute muscle size was not a factor. However, having said that it is likely that psoas major muscle size in elite sprinters is a key attribute to generating speed. In an RTE documentary on Asafa Power (former world 100m record holder with 9.76 seconds) it was discovered that his psoas major was twice the size of that of 10.02 Japanese sprinter Nobunara Ashara (5). To be continued 1) J Strength Cond Res. 2009 Sep;23(6):1633-6. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b2b8aa. 2) Above: Instr Course Lect. 1995;44:497-506. Motion Analysis Laboratory, Gillette Children's Hospital, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA. 3) Joes Scott: http://speedendurance.com/2013/01/21/3-reasons-the-squat-is-not-the-cornerstone-of-strength-training-for-sprinters/ 4) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006 Dec;38(12):2138-43. 5) RTE documentary (available on youtube) http://hight3ch.com/the-science-behind-asafa-powells-speed-documentary/ Jargon Buster Psoas Major: Long muscle that runs from the spine across the pelvis to attach onto the thigh bone. As part of the hip flexors it functions to lift and externally rotate the leg.

I regularly use drills and runs with the sprinters and jumpers holding a light bar overhead. In the video below I explain the purpose and protocols I use for fast running using a bar held at arms' length.

I have used these methods for the last couple of years to great success. The drills and runs improve posture, technique and speed and can potentate performance. So it's a win, win, win and win scenario. Take a look at the video content to get more information. The bars we use are readily available - see amazon link below too. You'll have heard me talk about about eccentric training on this blog or on my YouTube Channel. This is the type of specific work which will improve your reactivity, your sprint speed and your jump power.

Think of an eccentric muscular action as like stretching out a spring - if you did this the spring would store a huge amount of energy. Energy which will be released when the spring is let go and it recoils at super-fast speed. In our events the stretch of the spring as noted reflects the eccentric muscular lengthening action and the release the muscular shortening concentric muscular action one. There's much research that indicates that improving eccentric capacity will improve concentric capacity - hence it's crucial to train this muscular action. There are lots of ways to this, for example, you can do specific drills, some being more jump orientated and some more sprint orientated. You can also train eccentrically with weights. If you did this the focus would be on the lowering phase of the movement. For example, when performing a squat you could slowly lower for a 4-5sec count before (or not and leaving the bar in the racks and having helpers lift the bar back to the starting position) extending the thighs to return the weight. It's actually possible to handle more weight eccentrically then concentrically - up to 25% plus more in fact. We regularly include eccentric training in our workouts - you'll see two members of the u20 squad doing what I call "Jump forward, block and jump" jumps in the image. The athlete performs a medium length low height forward jump and then explodes vertically upward. The girl is performing the first part and the boy the second part in the image. Checkout the latest video on my YouTube channel to find out more and to see this drill and more - all designed to improve eccentric capacity. https://youtu.be/zYQRoH8Y-JM And if you needed a reason to eccentrically train: when triple jumping out of the hop the hop leg has to withstand and return up to 20 times body weight in milliseconds. Eccentric capacity is therefore vital. ----------------------------- CONSIDER BECOMING A MEMBER OF MY YOUTUBE AND HELP THE CHANNEL GROW! Many thanks to those that have become channel members at "Supporter" or Coach-Athlete" level - it's much appreciated. If you'd like to find out more about memberships and how you gain access to exclusive content then follow this link: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCyVAgma7MDT1Wqzw40Mb13g/join At Coach-Athlete level there are 10 videos on various subjects that will be particularly useful to coaches. There are videos on Training Planning, Training Transfer, Speed Phase Development, Overcoming Common Coaching issues with young sprinters and jumpers ....

It's taken a while but I finally pulled together the third issue of The Jumper. It's packed full of articles that should appeal to jumpers coaches and fans of these events alike. We've articles from top coaches such as Nick Newman, who's based in the US at USC as jumps and coach - Nick talks about his approach to jumps coaching. You can get his book from Amazon.

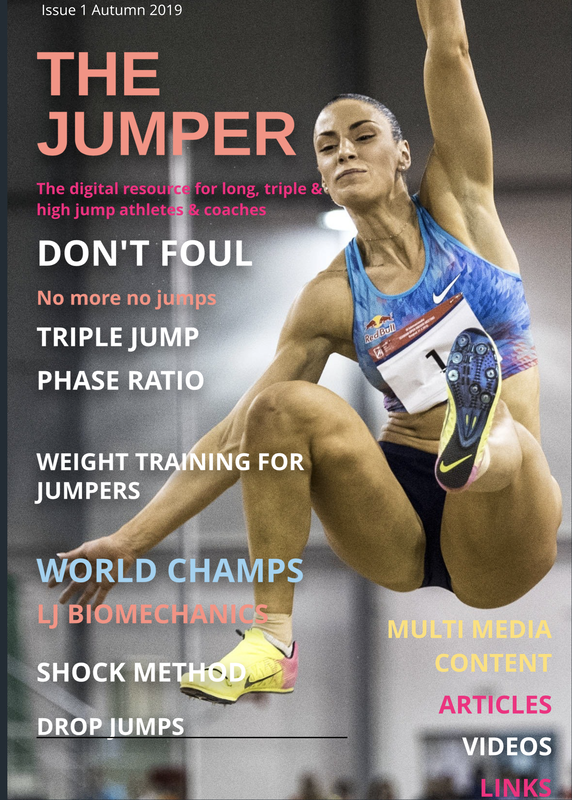

Then we have an article from Nelio Moura who has coached two Olympic long jump champions ... yes two. Nelio shares with us his tips on how to coach the long jump take-off. Top sprint coach Jonas Dodoo shares with us his tactics and technical tips for developing speed. Speed is something that all long jumpers and triple jumpers crave so this is a must read. Jonas's' article is part of a larger speed special, where we delve into numerous aspects of speed development, such as acceleration. The issue includes it's usual mix and there's our social media watch, where we single out great pages and channels and podcasts for you to scroll to. This issue was supported by Neuff - athletic equipment suppliers, so do check them out. There are some great offers from them (and other brands in the magazine). From Neuff you can get a Power Pack which includes sled, stretch bands and med balls and was part selected by your truly. It's a great combination of items that are actually really useful and applicable to sprinters and jumpers. To get hold of the issue for FREE, all you need to do is click on the image. It will download from the web and from there - should you want - you can download it as a PDF. Links to the various media will work in both formats I must be somehow getting better at making videos as I was asked by leading athletic equipment supplier NEUFF to produce a video on acceleration for them. In it I talk about the value of developing acceleration for all athletic events and I also take a look at some of the means used to develop it - such as hill running, harnesses and sleds. Technique is also considered - such as body angles and heel recovery. I also consider the land, for example, which should be placed on a sled and how too great a resistance can negatively affect sprinting biomechanics. To hopefully provide some clarity I also explain why adding a heavy weight to a sled can also act as a conditioning means for the more senior (training mature) athlete, Let me know what you think of the video. And if you're looking for sleds, harnesses and other items of athletic kit for all events do head over to NEUFF. FOR ALL ATHLETIC EQUIPMENT: PLYO BOXES, MED BALLS, THROWING IMPLEMENTS, SLEDS AND STARTING BLOCKS GO TO NEUFF ATHLETIC GET FASTER, IMPROVE STRENGTH & RECOVER BETTER WITH BIOELECTRICITY If you're based in the US then follow the LINK and sign up and SAVE 30% on the MiTouch I've found the device helps with recovery and can improve performance by stimulating fast twitch muscle fibre and improving motor learning. The MiTouch uses 5 apps and 3 types of bioelectricity to achieve its results.Check-out the affiliate link above. And for more on the device SEE BELOW Recently I was asked to do a session for Ireland Athletics, This involved two days in Athlone working with their top long and triple jumpers. As part of my tasks - I produced some course notes - as it were - to support the athletes and coaches learning. Well, I got a little carried away - partly as I know how to use an on-line multi-media magazine creation software programme (Lucid Press). The consequence was more magazine that power-point presentation. So, I thought I would further work on The Jumper and then release it to a larger audience. You can click on the image to view what I have created and there's also a short video of the content embedded into the page too via YouTube. As of today after not too much promotion 500 people from around the world have taken a look at The Jumper. Should support be forthcoming (I have set up a Patreon page), then I may do a further "issue" and ask (and hopefully pay) other coaches from the jumps community to contribute. Let me know what you think. Within the first issue of The Jumper are: My thoughts on how to piece training together Long and triple jump run-up accuracy tips Weight training for the jumps - limitations and potentialities Plyometrics and specifically drop jumps Links to The Triple Jumpers Podcast The Jumper also contains links to some of the videos on my YouTube channel which further illustrate what's being talked about in some of the articles. Again do let me know what you think. Is the title of this video click-bait ... ??? I don't think so. To get the most from your long, triple and sprint conditioning what you do away from the pit or the track needs to be transferable and relevant. There are many who swear by weight training and "need" to lift weekly - however, there are many who lift much less sparingly without their performances suffering. and in fact improving. If you are a regular reader of this blog or watcher of my YT channel videos you'll know that I don't place weights at the top of my "conditioning hierarchy". I'd rather spend time working on technique and speed and using plyometrics and sets of different sprint drills to develop what's required. I do however, see weights as having a role and that's to create robustness - that required to withstand injury (but note that this can also be achieved via many other means such as Swiss balls, and body weight exercises). I also value weights for the more conditioned athletes in the group and in particular utilise Triphasic methods - that's combining eccentric and isometric weights exercises with the much more common - and dare I say after a while, less important - concentric one. Also, by combining weights and plyos into a workout (Contrast/Complex training) you are more likely to get a heightened fast twitch muscle fibre and motor unit response - so this is something that we do regularly. The video below goes into more detail about my thoughts on what weight training to do to really improve your sprinting and jumping. It also looks at the limitations of a more traditional approach. MY OPINION As a coach I know how important accurate timing is. In my primary event the long jump you really want to know how fast the jumper is travelling into the board over the last 10m, for example, and also importantly what their flying 20m and standing 20m sprint times are. And for the 100m sprinter you might want to know 0-10m, 10-20m, 20-30m and 40m times. The problem is how can you do that with a stopwatch and without the type of kit that the IAAF rolls out at championships? Enter Freelap the timing system which offers a very neat and extremely accurate (to 2-milisec) solution. I've used the system for over a year now and have found it to be a great motivation for the athletes. As soon as those TX Junior Pro Timing pyramids are placed on the track or run-up the guys really respond and run as fast as they can. So, not only is there the benefit of accurate timing but also of motivating higher intensity from the athletes. Win-win I guess. The system is also easily set-up, very portable and has great consistency of operation. If you are interested in buying a system ... Please email [email protected] to discuss bespoke options and prices. The video below will showcase more Some further thoughts on use and my experiences ...

Like all tech the best way to learn is to play around with the kit to gain familiarity - once this is done it's important to consider and note the following. The settings on the Tx Junior Pros (transmitter pyramids) - these need to match what you aim to time. Here are some examples: For a standing sprint with just end time required, the end transmitter is set to "finish" and the TX Touch Pro (start button) is used to start timing. This is a black disc with a button that is depressed with the thumb which is released when the athlete starts, thus triggering the system, For flying times you need to set one TX Junior Pro to “start” and the end one to “finish”. The time will commence after the athlete passes the first transmitter. For track intervals, for example, 200m reps place one Tx Touch Pro at the start set to start and one TX Junior Pro at the finish set to “finish”. Start your session. Don't walk back past the TX Junior Pro at the finish as this will trigger the system when not needed – of which more later. You need to keep a 1.5m radius around the TX Junior Pro when wearing the FX Chip BLE (transmitter - which is the size of a small digital watch and fits on the athlete's waistband of their shorts/tights). For improved and consistent accuracy you need to set the Tx Junior Pro receivers 80cm off the point/points you want to measure at for sprints, hurdles, intervals and long/triple jump. Why? The Tx Junior Pros pick up and store the speed of the moving athlete 80cm before them - thus, over a sprint you could have a time “inaccuracy” of 160cm with the start and finish accounted for, if you don’t position as instructed. The “add-on” 80cm also applies to split-time positioning. Because of the Tx Junior Pros also 1.5m operating radius, freelap can time two athletes in adjacent lanes, which you can’t easily do with most accessible to athletes/coaches other timing systems (which can also take up three lanes to record an athlete in one – what with their tripods). You will need another FX Chip BLE to do this. The app is an objective systematic coaching “diary”. It stores the times from the session of all the athletes and does this historically, so you as coach (and the athlete)s, can track their progress. You can specifically name each session and its content. (Note: all the training group can download the Myfreelap app and see their performances.) It’s even possible for the coach to be at home, with the app open, and to be able to “virtually” see a session unfold. You give the freelap system to your athletes, they set it up as required, do the session and you’ll see how they are performing (hook this up with facetime or a wattsapp video and you’ll be even able to see the session too. - this is something I’ve yet to try! |

Categories

All

Click to set custom HTML

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed