|

Click to set custom HTML

If you watch some of the videos I've made on coaching for my youtube channel you'll have noted that a couple have created some debate. The main subject of contention surrounds the use of weight training to improve athletic performance. Last week I set about trying to make a short video that covered some of this. It's quite daunting trying to shoehorn information into a short video (turned out to be 8 minutes long) and also get what you are trying to say over in a clear and informative and hopefully not too boring way!

The video which you'll find below in this post covers: What type of weight training athletes should be doing What are the best lifts How to target fast twitch muscle fibre (I also provide some info on fast twitch fibre types and how it is recruited, which is important for when it comes to maximising the transference of gains in the gym to gains in performance. A brief overview of periodisation (training planning) as this is integral to maximising the transference of strength and power gained in the weights room to actual event performance. Over the years I have become slightly frustrated by the emphasis that can be placed on weight training. If only the same value was placed on the learning of optimum technique and rest, recovery and adaptation, for example. Going into the weight room is not a magic want, it will not it will suddenly turn a 7m jumper into an 8m one. It can help, but there is a lot more to it than that. The video explains much (hopefully), but I want to note one area that may be key - largest size fast twitch motor unit recruitment,neural and physiological adaptation. A jumper relies on fast twitch (type 2) fibres to jump far. Therefore it's these fibres that need to be targeted by a training programme (in and out of the weights room). In an interview with Tudor Bompa - one of the older school experts on strength development and periodisation, he talked about something known as the periodisation of strength and MxS (max strength training). Through his practical coaching and research it was discovered that relatively low volume but heavy weights (85% of 1 rep max and above) simulated the neural system to recruit the largest more power producing amounts of fast twitch fibre and it was regular inclusion of such training methods into a training programme that elicited gains in power. Thus sessions such as: 4x4 @ 86% 1RM; 4 x 2 @ 90% 1RM... Plenty of rest must also been taken between exercises so that 'maximum attack' can be used. It's this intent which is key. The athlete has to be in the zone and fired up. Although this way of training is relatively old school, it's not as widely used as it could be, with athletes doing workouts that would be more suited potentially to a fitness model or a body builder i.e. 8-10 reps over 4-8 sets, for example. In the video I also talk about the hormonal response of weight training and this has to also be taken into account when constructing a weight training plan which will be of benefit to athletes. The sessions I mentioned that could apply to a fitness model, for example, produce a greater muscle building response (through the greater production of growth hormone and testosterone) which can affect muscle mass and power to weight ratio. I say more about this in the video. There's a lot to getting the most out of a weight training programme designed to improve athletic performance. It needs more than one blog post or a video to get everything across. Over the following months I'll hope to go into more detail and touch on some other themes. Do note: these are my views although subject to research, interview and practical implementation, other coaches will have potentially divergent views.

2 Comments

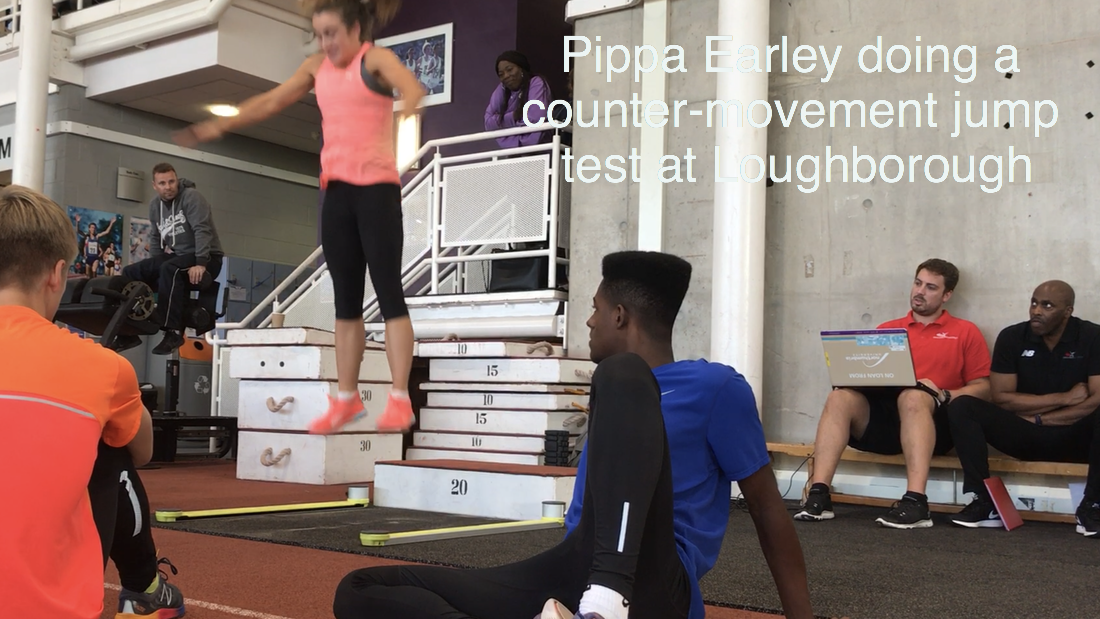

A few weeks into the season and athletes are beginning to get fitter and are able to handle more specific and heavier loadings. Many coaches will implement a testing programme to analyse the progression of their athletes. I've not always been a great one to do tests, not because I don't believe in them, but more due to the fact that you've got to test the right qualities with the right tests and not just test for the sake of it. The athletes have also got to be able to perform the tests comfortably. When I say comfortably they have to have familiarity with the test, otherwise you're testing immediate learning of a skill, rather than the skill itself. Now there are tests which have a generic status such as standing long jumps and vertical jumps. These common tests don't require real prior preparation. However, athletes who have trained using these tests (or similar) are going to have an advantage. It's also likely that coaches and athletes will compare to the well-established norms that exist for these tests for comparison purposes. Be warned you may be thrown a little off the scent if you do this. How come? Well, what if one of the athletes you coach is not great at accelerating then in all likelihood they will not perform so well on standing start tests i.e. the standing long jump. Conversely you may have an athlete achieve a great distance, but then be left scratching your head as to why they can't actually long jump the distances you think they should be able to. The answer because they are unable to produce power in a short space of time at great speed as is needed for the long jump take-off. I believe it's therefore key for the coach to devise tests that work for his or her athletes and to even make these specific for each athlete. A long jumper will not necessarily have the same bounding ability as say a triple jumper. So a 20-metre bounding test may show that the long jumper is not as good as the triple jumper, even though the long jumper is elite. A better test for the long jumper (and indeed the triple jumper, plus the bounds test) may be speed over the last 10 metres of their run-up. The long jumper needs to be able to generate one high powered and very quick take-off the triple jumper three with minimum drop off in horizontal velocity. Too much bounding for a long jumper, in view of preparing for a bounding test, may therefore be counter-productive in that respect too, due to the slower ground contacts involved. One of my group - a triple jumper - needed to improve on his hop, we therefore began to work on this using what would become a test. This involved the aforementioned 20 metres bounding, but one of the 'tests' was 2 hops and 2 bounds, this places the jumper onto their same hopping leg, thus allowing him to really work on the rotation of the hop and a transference onto the step phase. Over time the number of bounds (and hops) needed to complete the 20m distance reduced. Note we did increase the run on as the season neared and reduced the distance for the hops and bounds to 15m, making the test even more specific. This specificity is also important and the 'bringing along of the athlete's readiness' for the test so that they can optimally and safely perform it. To sum up then I believe it is very important to assess and understand just what you want to achieve when testing in particular training mature athletes. The tests also need to be learned by the athletes and they should have the required skill to perform them, they also need to evolve and be related to the time in the training year. LONG & TRIPLE JUMP MASTERCLASS - this Nov I will be running a long jump master class with coach Tony Gain on Sunday the 19th November for long and triple jumpers and coaches interested between 12.30-2.30PM. Details below, if you wish to book a place please send an email to [email protected]

Click to set custom HTML

|

Categories

All

Click to set custom HTML

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed