|

THOUGHTS ON HURDLE JUMPING & BLOCKING JUMPS

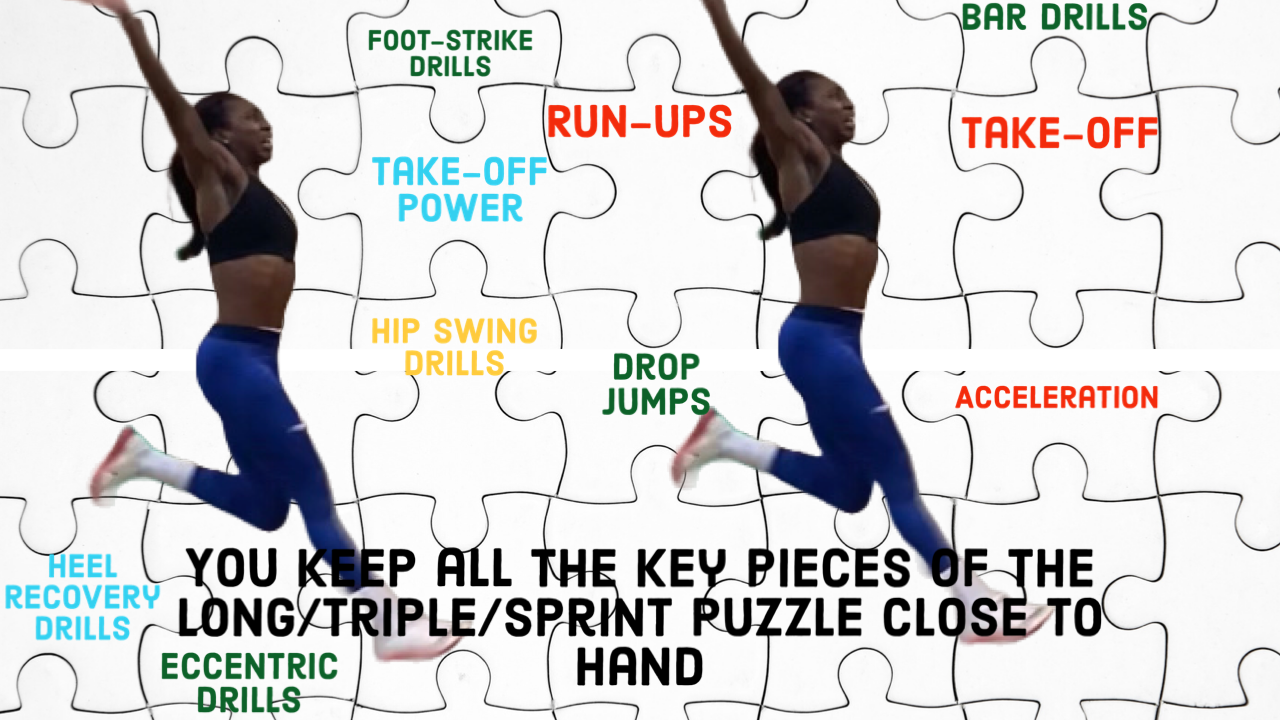

If you want to sprint faster or jump further then you need to do plyometrics. Here are two jump exercises (the blocking version is not strictly speaking a plyo - as it only emphasises the braking part of a jump. This is the element which includes the isometric and eccentric part of the plyometric "stretch” before the concentric “reflex"). Hurdle Jumps I only use hurdle jump occasionally in our training. This does not mean that they don't have a value. What is important is to focus on - as with all plyometrics (within reason) - is speed of contact. The jumper does not want to spend too much time on the ground. This can be an issue with prolonged use of hurdle jumping. You may want to lower the height of the hurdles so that the ground contact speed increases. A combination of lower to higher hurdles can help with this - but potentially higher to lower in sequence could be a better option. There are also other options, for example, including a drop jump take-off between each hurdle (more in another post). Or just using lower hurdles and really monitoring contact time… Periodisation and Ground Contact Time It's possible to periodise hurdle jumping. This is something that the elite Chinese jumpers do, for example. So, despite being 8m and 17m male long and triple jumpers respectively as examples, they may jump over much lower hurdles than expected. They also start the training year with higher hurdles and slower contacts and reduce hurdle height and speed the contacts up as the competition season approach, The contact time on the long jump board for the take-off is around 1100 milliseconds. Ground contact time for a hurdle jump can be much quicker 1300ms-1600ms. Also hurdle jumps can be doubled-footed and of course the long jump take-off requires a single contact. It is important to try to be as specific as possible with your jump and sprints training - within reason. Occasional sessions of less specific work won't do harm i.e. impair performance in the long-term. I'm referring here to the main body of your training - as of course there will be other activities that can be included in a training programme which are not directly related to jump performance - weight training, for example, being another. It's the core drivers of your training programme which matter. Blocking Jumps The key with blocking jumps (as shown in the video) is to stop the downward movement (acceleration) as quickly as possible. Also with minimised knee-bend. In the video Bora is bending her knees a little too much and cushioning the impact. Much research has shown that improvements in eccentric ability improve take-off/take-offs and energy return for the long and the triple jump.

0 Comments

In this video from my YouTube channel I discuss peaking i.e. when an athlete will have their best years - not a seasonal performance peak or peaks.

There's also a focus on Jonathan Edwards the current world triple jump record holder whose record was set over well two decades ago. Edwards was very much a late developer breaking the world record when he was 29 years of age, for example, and still jumping close to 18m at 35. I provide much information on him and to this extent I must reference the excellent book Triple Jump Trail Blazers The book tells the story of the triple jump from the first Olympic Games and focusses on all the key players male and female in the development of the event including the world record holders. It really is a great read and one which lovers of track and field and the jumps will appreciate. TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE BOOK CLICK HERE Video Timeline: 0.00min Intro When will you be at your peak for long and triple jump? The majority of the world's best will be in their mid-late twenties - but of course there will be exceptions 0.23min Research indicates that it is possible to jump big at young ages Jumps have more outstanding performers 0.42sec For the majority it takes time You have to work on the talent you have"Very few elite u17 and u20 athletes will go onto win World/Olympic medals" 0.55min The coming together of factors that will enable you to reach peak performance Training environment, coach, training group, facility, family support. I say to my young athletes it's a developmental journey. You won't (normally) jump really far until you are in your mid twenties 1.40min Doing the training which is right for you I have a proven training method with young (and older athletes). Data shows that jumpers who show speedy progress in their latter teenage years will often develop into really talented jumpers 2.40min Jonathan Edwards focus Went from 16.01m at 23 to 18.29 at 29. He jumped 17.92m at 35! Checkout Triple Jump TrailBlazers book 4.28min Jumping well into the late twenties and beyond A focus on Paul - one of my squad members - who now 35 has jumped over 7.50m nearly every year since the age of 23. He is a great example of how to train diligently and "professionally" I talk about using a "less is more" approach and of not thinking that doing more will actually help. Tap into all those years of prior training and be smart with your choices and ensure optimum rest and recovery to minimise injury. Checkout the recentTrack & Field Performance podcast by Colm Bourke featuring Boo Schexnayder Which talks about training approach and more for older athletes too 5.44min Summing up Please subscribe to the channel In this video I provide you with some information on how to best condition jumping with jumps! There is a focus on the triple jump but the info will be applicable to the long jump and to sprinting.

|

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed